From the wealth of information about Esper in Bulgaria in the previous chapter we are now reliant on scraps, mentions of Esper in other people writing and official and other records.

After the events in Bulgaria Esper and Ekaterine moved briefly to Romania. There she sent a telegram to Lev Tikomirov in Paris that they were leaving and would be returning to Paris. In Esper’s whole writing of his time in Bulgaria he does not mention Ekaterine once. But from the writings of Lev Tikomirov we know she was there with him. He says that she enjoyed the life of being the wife of an important person, the whole time was good for them both and the only thing to spoil it was that it lasted only a short time.

On their return to Paris in March 1887 they were better set up financially. The lived in Neuilly-sur-Seine just outside Paris. Tikhomirov seems to imply that he was less involved in the work of the revolutionary group than before. The efforts of the expatriate Russian community to print leaflets to send to Russia had largely come to an end. Some people had returned to Russia and subsequently been arrested, the organisation had fallen apart. Lev Tikomirov describes this in his memoirs. The Russian secret police, the Okhrana, were infiltrating the revolutionary groups creating mistrust and doubt. This eventually led to mental brake-down of Lev Tikomirov, he eventually recanted his revolutionary position and sought a pardon from the Tsar.

Esper who arrived back in Paris in March 1887 seems to have avoided these problems. He appears to have settled into a domestic life with Ekaterine using the money he had gained from his work in Bulgaria.

He may have been unaware of the efforts of the Russian government to make the whole of Europe a hostile place for the anarchist nihilist Russian expatriates. Russia was putting increasing pressure on Bulgaria for employing such people. Some were forced to flee from Switzerland, France and other European democracies as pressure was applied by Russia. There were strong informal links between the Russian secret police and the French police.

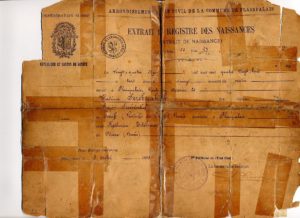

In October 1888 Esper and Ekaterine travelled to Switzerland. While there Ekaterine gave birth to their first child, Vladimir. The birth certificate for Vladimir shows his birth as the 24th March 1888, and the address of the family at the time as Plainpalais, Route des Acacias 20, a suburb of Geneva. The certificate shows Hesper Serebriakoff as the father, the details of his occupation have been destroyed by the use of tape to hold the certificate together, but the words Lieutenant and Russie can still be made out. He is shown as coming from Ostroff (province of (unreadable)) Russie. Ekaterine is shown as Katherine Tetelman from Odessa (Russie). The certificate is dated 3 April 1888.

A story was told about the occasion of the birth of Vladimir, the truth of it cannot now be verified. It seems that Ekaterine and Esper went for a boat trip and while on the boat Ekaterine slipped and subsequently started labour. Whatever the truth of that it is not known why Esper and Ekaterine were in Geneva. It may have been for their health.

Later that year in September Lev Tikomirov published an article in Narodnia Volia’s Geneva journal setting out why he ceased to be a revolutionary. On the 12 September he petitioned the Tsar to be able to return to Russia. This move by Tikomirov came after considerable effort by Russian agents to undermine him and also a great shock to the revolutionary community. Esper wrote an open letter to Tikomirov pleading for him to reconsider. That letter is now held in the British museum.

The couples second son Anatoly was born in Paris on the 25th April 1890, they were back in Neuilly near Paris. Then in 1893 a daughter, Anna, was born in Paris.

In 1890, a periodical, The Universal Review published an article by Esper (written as Hespėre) about atrocities in Russia. The publication is dated 7th May 1890 and the article is written in French, though there is a short passage describing who Esper is. That passage in full is;

The Opinion of Hespėre Serebriakoff (A Russian exile).

M. Serebriakoff is a Lieutenant in the navy who took part in the Russian revolutionary movement as a member of the military organisation known as the organisation of the “Will of the People.” He was arrested in 1883 (his friend Soukhanoff had previously executed), but managed to escape the same evening, and took refuge abroad. He then took part in the war between Bulgaria and Servia as commander of the Bulgarian fleet, in which service he was decorated. The above facts have been communicated to me by the translator, a Russian exile intimately acquainted with M. Serebriakoff, who apologises for the poverty of the French translation from the original Russian, which was greatly hurried in point of time.

This gives a slightly different version of Esper’s escape from Russia. However this version is via at least one third party and possibly across a language barrier. The version quoted earlier is from Esper’s own direct writings and probably more accurate.

At some time during 1892 Esper designed a slow burning wood stove and applied for a patent. A patent was granted for France, Belgium and England on the 3rd October 1892. The patent was granted on the 12 December 1893 for America, the application says it was granted to Hesper Serebriakoff of Paris, France.

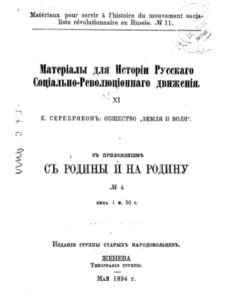

Esper published this book in Geneva in 1894, it is a history of the Narodnaya Volya revolutionary movement.

At some time in early 1894 Esper and his family moved to England and London. In March and April he was staying with Stepniak, real name, Sergius Mikhailovitch Kravchinsky, in Hammersmith. Stepniak had escaped Russia after assassinating the head of the Russian secret police in St Petersburg in 1878. He was part of a group of Russians who were using the reading room at the British library and he acted as a referee for Esper when he applied for a ticket for the library.

In the first few months of 1894 George Bernard Shaw was working on a play that we now know as “Arms and the Man”. At first the play was to be about a war, any war, ‘nothing but a war with a machine gun in it’, the tentative title was “Battlefields and Boudoirs”. However he took advice and settled on the Serbo-Bulgarian war of 1855. He place the action in a Serbian family home. On the 17th of March he took his play to Stepniak to read and discuss it. However much to Shaw’s horror Stepniak invited the Admiral of the Bulgarian fleet to read the play. Shaw was so nervous that he did not catch the admiral’s name. The name was later found to be Serebryekov. The story of Esper in this retelling is somewhat changed[1], but it reports that Serebryekov had commanded the Bulgarian Danube Flotilla before being suspected of nihilist sympathies, then escaped to England and became a farmer. How much of this wrong information is a problem of communication or a deliberate covering of the facts to avoid police monitoring or simply the retelling through different people. Shaw later complained that he had to change the play considerably, moving the location of the action from a house in Serbia to a house in Bulgaria to make use of the local information provided by Esper. I think it is interesting to note that the principle character in the play is a Swiss Mercenary soldier, and that Esper was serving in Bulgaria using a Swiss passport also Shaw names the principle character Sergius, apparently after Sergius Stepniak. Later Shaw wrote a letter to the manager of the Playhouse Theatre asking for tickets for the first performance to be sent to Stepniak and the Bulgarian Admiral, “who gave me the local colour”.

In the summer of 1896 from July 26 to 1st August the forth congress of the Second International was held in London. This was a meeting of international socialist workers and Trade Unionists. Esper was in London for that event. He was initially listed as a delegate for the Russian group, on the basis of his contributions to Narodnaya Volya. However that congress is considered to have been marked as one of extreme arguments between and within the various national groups of delegates. Esper was subsequently listed as a delegate of the French group where he had standing as a journalist.

Sadly, later that year Esper and Ekaterine’s daughter died. There is a death certificate for an Anna Serebriakoff aged 3 who died of Meningitis in the Cottage Hospital, Dartmouth, on 25th September 1896. What the family were doing in Dartmouth is not known, my attempts to find out more about this have so far failed.

Background.

It is difficult to fully understand Esper’s role in Russian émigré community in the 1890s. It seems at that time the early British socialist movement was making contacts with the group and using their experience to motivate their own efforts. Certainly Esper is mentioned in many commentaries at the time and he is frequently identified in subsequent histories of the period. For example, in the histories of George Barnard Shaw. One such history, “The Only Hope of the World, George Bernard Shaw and Russia” by Olga Soboleva and Angus Wrenn published in 2012, though it gets the dates wrong (it places the first meeting of Esper and Shaw in 1884. The purpose of that meeting was to discuss Shaws play “Arms and the man” which takes place against the background of a war that took place in 1885. Other commentaries place this first meeting in 1894), identifies Esper as one of the important figures along with Prince Kropotkin, Sergius Kravchinskii and Olga Novikoff, (Page 14). Other writers on Shaw, Holroyd for example, also mention Esper’s role. There are the writings of Esper in other publications such as, ”The universal review” volume 7 May 1890, with an article by Esper about atrocities in Russia. Michael Holroyd has a description of the first meeting of Shaw and Esper.

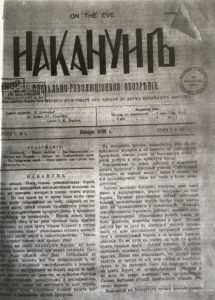

But now we just have these histories and the knowledge that Esper was editing revolutionary magazines which makes it difficult to fully appreciate the extent of his role.

About a year later the Russian government put increasing pressure on the British to prosecute Vladimir Lovivch Burtsev. Burtsev had published an article calling for the Tsar to be killed. Burtsev was a particular target for the Russians after he had successfully exposed several double agents, Russian police spies, in the revolutionary groups. The British police had been watching Burtsev and the others. There is a record, reported by Robert Henderson a historian, quoting from a report by Inspector Melville of the Metropolitan Police,

“13 September 1897 (Burtsev was) living with the “notorious Nihilists & Anarchists – Serebriakoff, Tcherkassoff, and Zhook at 12 Osman Road, Shepherd’s Bush (Hammersmith)”.

Inspector Melville was one of the first officers of what came to be special branch of the Metropolitan Police, and later became superintendent in special branch.

Burtsev was later arrested at the reading rooms of the British library and was tried and sentenced to 18 months hard labour.

In the Houghton library at Harvard University there is a collection of letters to Feliks Volkhovskii , another revolutionary. How these letters came to be held in the collection I don’t know. There are three letters one to Esper and another from Ekaterine. The third is a bit of a mystery.

The letter from Ekaterine is dated 9 July 1897 and gives her address as 16 Westcroft Square Hammersmith. She is writing to Feliks Volkhovskii thanking him for a parcel and that her children were grateful for the stamps he had sent. She goes on to complain about her landlord, Klement

Verzhbitskii, he is selling up and leaving the house and they must look for other accommodation. But finding other accommodation is difficult because everywhere they try will not allow children. She writes the letter in Russian but uses English to exclaim “No Children, No Children”. She finishes by saying that they are moving the next week and will write with the address.

The letter to Esper is a postcard from a person called M Krummer. It is dated 12 August 1901. It is written to an address in Montem Road, Forest Hill, South East London. In the letter Esper is asked to thank two people on the writer’s behalf and then says that a Comrade Gan will call to see Esper on his way to Paris and he “will communicate something to you personally”.

I have been unable to identify the M Krummer or the Comrade Gan. It is likely that these are pseudonyms, the Russian revolutionary community must have known that they were being watched.

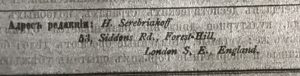

The third letter is a bit of a puzzle. It is written from 53 Siddons Road address where Hesper lived, it is undated, and it is signed by G. Yefets. I do not know who the person Yefets is, it is odd that the letter is listed in the Houghton Library as being connected with Hesper or Katherine Serebriakoff. Though the handwriting is similar to the letter from Katherine, so maybe it is Katherine or maybe it is a lodger staying with them.

In 1898 Ekaterine’s 4th child was born, a son Pytor, or Peter.

In 1901 the family were listed in the census at 17 Montem Road, Forest Hill, Lewisham, South East London. The entry shows Esper (spelt this time as Hesper), 47 Editor of a Russian paper, working from home, born in Russia and a Russian national. The entry for Ekaterine uses the name Katherine, gives her age as 37, born in Russia and a Russian national. The entry for the eldest child, Vladimir, uses the familiar name Volodia, age 13 born in Geneva, Switzerland. The next entry is for Anatole, aged 10 born in Paris France, then finally Peter, 2, born in Forest Hill London.

Esper wrote at least two books during this period, in 1899 “On the Destruction of the Standing Army” and ‘Company “Land and Freedom” 1894’ and edited other periodicals.

[1] A biography of Bernard Shaw, Volume 1 1856 – 1898 by Michael Holroyd 1988. ISBN 0701133325.