Anatoly’s work with Muskrats was quite successful, some had been released into the wild around several lakes on the Solovki Island. This was apparently the first time that there had been a successful breeding and acclimatisation programme in the Soviet Union. Anatoly’s role in this was greatly appreciated.

Ekaterine notes in her diary that she had a message from a friend who had been visiting the camp. By chance Anatoly had been bringing papers relating to the Muskrat to the camp commandant and the visitor thought that Anatoly was treated with great respect.

On the 2nd of May 1931 Anatoly wrote to his mother about the possibility of parole, he wrote that he had been told by the authorities that he was free but that the papers from Moscow had not yet arrived. But it wasn’t until the 12 of January the following year that he was officially released. That was 2 years shorter than his original sentence. However in letters to his mother he indicated that he might stay in the area which he had grown to like. In the end however he did return to Leningrad.

Ekaterine’s diary reveals something of the excitement felt at the return of her son. She first received a phone call from Carl Tuomayen, the man Anatoly had been working for, in early January that soon Anatoly would be fully released. Then she received a short letter from a M. N. Sidorova saying that soon Anatoly would be home. Then finally in the evening of the 15th January she received a telegram saying “16th in the morning to come Toila”.

Ekaterine writes of that day,

“Peter did not sleep all night after learning that the train will arrive at 6am. At 4am he walked to the station. The train was two and a half hours late. About 10 Tolya walked gaily in my (our, with Filonov) room. Eight agonising years passed and Tolya was again with us. A silent joy and special calm filled me. He looked cheerful, though in the last 2 months he had worked tirelessly wanting to leave everything in order and pass on his experience to his deputies.”

On the 7th February 1932 Anatoly married Maria Nikolaevna Sidorova a woman he had met in Povenets, a small town between Leningrad and Solovetsky, about 600 kilometers from Leningrad. How he met her is not clear, she was the person who sent Ekaterine the brief letter to say that Anatoly was to be freed. He then set about trying to find employment and obtain a residence permit.

He travelled to Moscow to see his old boss, Tuomaynena, looking for an opportunity to take up fur farming. However the only place available was in Vladimir, a town near Moscow, but he was not registered to live there. Finally an invitation came for him to work in Kiev and he accepted it.

Ekaterines diary describes a farewell meal, present were Pytor, his brother, Pavel Filonov, Anatoly and his wife Maria Nikolaevna. Everyone was happy and Ekaterine made a little speech.

“Several years ago in this very room Tolya sat as an old knight at the crossroads, he thought about what road to go. Go left – lose the horse; Go to the right – the very abyss and – could not choose, despite the advice of his mother. Pondering his decision, he did not accidentally get into the Solovetsky nursery of fur-bearing animals, where he spent 8 years, having passed such a school of life, which will be equal to the end of the fifteen best universities. Now Tolya is back in this room, and I hope that this time he realises what he has to do. We, your mother, brother and I, people who completely believe in the party and the correctness of its great work, demand from Tolya that he understand this unprecedented titanic work of the party, after which millions of the best people go and follow the party with all the strength and energy to become the surest ally of the proletariat in its last decisive struggle, the struggle of the classes.”

To our understanding the last part of that speech seems strangely out of order. Accepting that it may have lost something in the process of translation nevertheless the references to The Party seem out of place at a family gathering.

One consideration is that the family were under observation. They knew that one of Ekaterine’s diaries had been stolen by a maid who was a spy. Although this happened some years before they would be well aware of potential dangers. If they felt that they were being spied and reported on they would ensure the entry in the diary followed the proper form.

Anatoly arrived in Kiev on the 13 March 1932 and was shortly joined by his wife. Later in the year they visited Leningrad to see his mother between 13 October and 7 November. During that time Anatoly wanted to become better acquainted with the Pavel Filonov and spent some time being taught how to draw by Filonov.

There is a gap in Ekaterine’s diaries between 20 February 1933 and 24 April 1936, but at some point during that time Anatoly returned to live in Leningrad. He became a member of the Academy of Science of the USSR and worked in the editorial office at the publishing house as a translator. He became interested in the history section of the Academy of Sciences and wrote an article entitled “Zoological Cabinet of Curiosities” in 1936. This article formed the first part of the work of recording the history of the Zoological Museum of the Academy of Sciences. He was a little uncertain about taking this job on but agreed to.

Anatoly started his work on recording the history of the Zoological Museum, which had some of its first exhibits from the time of Tsar Peter the Great’s travels through Europe. His first chapter which he titled “Zoological museums of Western Europe at the beginning of the XVIII century” sets out an analysis of the museums of Europe, and he develops an idea as to the underlying causes of the increasing interest in science.

The source for this information about Anatoly’s work has great detail about the contents of the three chapters of his work that he was able to complete. The source comments on his approach skilfully combining reasoning about general trends with a story about the details.

Things seemed to be going very well, in November 1936 Ekaterine writes in her diary, “Yesterday Toll and Maria came by wanting to celebrate the first appearance of his article in the Journal of the Academy. We sat up until 2am”. She had written in an earlier entry in July that Anatoly was working very hard, sometimes 12-14 hours a day.

In 1938 Anatoly’s work stopped, he was arrested for a third time. First Anatoly’s brother Pytor was arrested during the night of the 11th of February 1938. His property was confiscated and some of it destroyed. Ekaterine wrote “In the night of 11 to 12 February was taken Petya. After 7-8 days we learn that he is in prison on the street Voinov. (We were) Allowed to pay monthly 60 p (Kopek?). However, soon stopped accepting money.” She was told that Pytor was being held “10 years incommunicado.” That phrase was used to conceal the extent of the repression and generally understood to mean he had been shot dead.

On the 8th of June 1938 Anatoly’s house was searched and he was arrested on the morning of the 9th. He also was taken to the prison on Voinov Street. His wife was able to give him 60 p in early July and they learnt by the end of July that he was registered for the military prosecutors office on Herzen Street, and that an investigation was being conducted that would be finished in a month and a half. On the 5th of August Filonov took money to be given to Anatoly, but the money was not accepted. Again meaning that he had been shot.

The reason for their arrest seemed to lay in a census conducted in Russia in 1937. This census had originally been planned for 1933 but it was surrounded by controversy and delays and eventually it took place on the 6th January 1937. Some of the delays related to the questions being asked. Eventually Stalin removed some and simplified other questions and added one about the person’s religion.

The question about religion became critical. It was expected that most people would state that they were atheist. Some people thought that if they declared their religion they would be persecuted. Others thought that if enough people declared their religion the state would be compelled to open the churches. It seems that Pytor and Anatoly refused to answer the question, as about a million other people did. It was this that led to their arrest and execution.

Eventually because the census indicated that the population growth in Russia was significantly below what Stalin had been confidently asserting the results were never released. People were killed for no good reason. But it did not take much at that time of what is called The Great Terror to offend the state and receive the ultimate punishment. (And Stalin wondered where his population was!)

In October Ekaterine tried to find out what had happened to her sons. She wrote in her diary, “October 13, I sent Comrade Stalin and Beria a letter regarding my two sons.” She got an appointment to see the secretariat of the NKVD (The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) to plead her case. She later got a letter from the NKVD saying that the sentence i.e. 10 Years incommunicado, remains in force. She records that she felt ill that night.

The stress of these events on Ekaterine took their toll, in late November she had a stroke. Some sources say that she was taken to hospital. There Pavel Filonov went to fetch her and carried her home and nursed her, teaching her how to walk again.

She was still able to record her diary. She writes on the 30 December 1938,

“This afternoon, my daughter (in law) went to the Military Prosecutor’s Office to find out about Tole, her husband. She came back in tears, barely able to stand on her feet, I had to unlock the door of her room, she herself was not able to. When I brought her into the room, she, sobbing, threw herself on the bed. “Toll Died”, she said with a groan, when did he die? Why? Was he buried or not? Where to find the body? She cried, lying on a couch. I stood there comforting her as I could, thinking of the dangers of this event to my daughter (in law) and how to behave with it. Neither she nor I can believe that Tolley is dead. He was healthy, well fed, extremely hardy and undemanding. It is difficult, you cannot somehow believe that he was gone forever from his mother.

Pavel Filonov kept a diary and records that Anatoly’s wife could not come to terms with his death and held to the idea that “How could he die when I’m waiting for him every day!” A death certificate was issued dated February 2 1939, it stated that Anatoly died on the 8th July 1938, and the cause of death was pneumonia. Apparently the issuing of such certificates was very rare.

From the present day records of the FSB (Russian security service) they show that Anatoly Esperovitch Serebriakoff died on July 8th 1938 in the prison infirmary of the UGB NKVD AO of heart failure. On the 1st August 1938 the investigation onto Anatoly was dismissed due to the death of the accused. The Prosecutors Office of St. Petersburg on 21 March 2003 exonerated A E Serebriakoff.

Ekaterine’s entries in the diary become increasingly hard to read, sometimes very repetitious, others totally unreadable, she even writes “My voice is much better, but I still understand very little, I have to listen very attentively”. It seems that the stroke and the stress of dealing with the arrest and death of her two sons had hit her very hard.

Ekaterine did not accept her son’s death, it may be that she was not told of Anatoly’s death, she wrote in her diary on January 1 1940, “We all said will wait for Petya and Tolia. I think the war will be over, and in the victory no doubt my sons will be with us.”

Russia initially sided with Germany in the first year of the Second World War and it wasn’t until the 22 June 1941 that Germany invaded Russia. One of Germany’s main military thrusts was towards Leningrad. They laid siege to Leningrad on the 8th September 1941. Conditions inside Leningrad became terrible with a great shortage of food as well as bombardment by enemy guns.

Filonov shared his food with Ekaterine. He died of starvation on the 3rd of December 1941. Apparently his sister, Yevdokiya Nikolayevna Glebova helped put Ekaterine on a sled and pulled her behind the sled carrying Filonov’s body to the cemetery so that she could pay her respects.

In May 1942, Ekaterine died, she was 78 years old. She had been in contact with her oldest son Vladimir until 1936, or that is the last entry in her diary relating to him.

Filonov’s sister Yevdokiya Glebova managed to safeguard all Filonov’s work as well as Ekaterine’s diaries and today they are in the Manuscripts Department of the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg. Filonov was a significant artist and today his role in the Russian Avant guard art movement is highly regarded, even if it wasn’t during the Stalinist period. His work however is not well known outside Russia because he did not sell it, so it is all in museums and galleries in Russia.

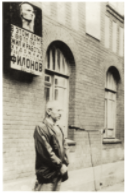

The apartment block where Ekaterine and Filonov lived, 19 Litratov Street, shown in the picture, is still there in St Petersburg, though today it seems to be a nursery school. In September 1996 a plaque was unveiled on the wall of the block to remember Filonov.