During 1905 a series of strikes and brutally put down marches and protests spread across Russia. The Tsar was finally forced to accede to allowing a Duma or parliament and a range of reforms including limitations on the power of the Tsar and a written constitution.

Back row: Ekaterine, Vladimir, Esper

Front: Anatoly, Pytor

This revolution of 1905 allowed émigrés such as Esper to return to Russia without fear of arrest. Esper and his family did return. But first they went to Finland living in Terijoki, which was part of Finland until 1947. They lived for about three years there. However Vladimir was left behind in England to complete his studies. He would have been about 17-18 years old and attending a university in east London studying engineering.

This picture was taken of the family in 1906. It shows Ekaterine and Esper with Vladimir between them, Anatoly on the left front and Peter at the centre front.

On his return to Russia Esper was engaged in working for the publication “Vestnik znanii“ [Herald of knowledge], mainly translating from English and French. He also translated many books including Darwin’s “Voyages of the Beagle” and Beecher Stowe’s “Dread, a tale of the great dismal swamp” (her second less well known novel after Uncle Tom’s Cabin.)

Vladimir completed his studies and started work at Siemens in Woolwich South East London. It is interesting to speculate whether the original plans for Vladimir were to complete his education then join the family in Russia. Or possibly he had no interest in a country he had never seen having been brought up in France and England. Certainly this disconnect caused problems for his brother Anatoly as we shall see later.

Whatever the original plan Vladimir stayed in England. He appears in the 1911 census twice, once at 12 Shacklwell Lane London N E, shown as visiting what appears to be another Russian family and also in St Pancras at 46 Sandwich Street London WC. He is shown at the St Pancras address as a boarder and several other young men are living there. At the Shacklwell lane address, the head of the house is Ludwig Nagel, 49 years old, an electrical engineer and a widower. He is shown as being born in Russia. He has 3 daughters, Marie, 21, Sophie 20, Olga 17. They were all born in Paris. There is also an Anatole Nagel shown as 0 years old the grand child of the householder. I can find no other trace of Ludwig Nagel, how Vladimir comes to be shown on the census as visiting is not known. But perhaps they are work colleagues, Vladimir is also an electrical engineer and because of their Russian background (and Ludwig’s three daughters?) he was invited to visit. Alternatively, they may have been in Paris at the same time as Vladimir’s parents and when they returned to Russia they asked Ludwig to keep an eye on Vladimir.

With Vladimir a young man living alone in London inevitably he met a girl. The story told by his son Victor is that every day Vladimir would travel on the Woolwich ferry to go to work at Seimens. On that ferry also traveling was a girl, Ethel Graham. On one occasion it was raining and Vladimir snatched an umbrella from one of his friends and offered to shelter Ethel. Of course one thing led to another and they were married in St Pancras London, in March 1912.

Their first child, Victor was born in October 1912 they were living in Camberwell at the time. Ekaterine travelled from Russia to see the new baby. This may have been the last time that Vladimir saw his mother.

EE Lazarev, E A Serebriakov, Gorsky, Exper. 1917 Petrograd

There were two revolutions in Russia in 1917. After the February revolution Esper joined one of the groups of Socialist Revolutionaries where he participated in the editorship of the newspaper “Narod” (The People). He was also Deputy Chairman of the executive committee of the temporary Vasileostrovsky Municipal Committee. He was also a lecturer in the cultural and educational department.

After the October revolution that led to the communist takeover, Esper left the Socialist Revolutionary party and concentrated on research and literary activity working as a researcher in Historical – Revolutionary Archives. He became a member of the commission of the Museum of the Revolution. He took part in the creation of exhibitions dedicated to the history of Narodnaya Volya and wrote a memoir about Piotr Lavrov. He became dissatisfied with politics, Ekaterine recorded in her diary in 1921, ‘Esper often stops me, “Do not tell me about politics, I want to forget about it, and you remind me”’.

Esper died on the 13th March 1921. He was 67. His grandson thought that he may have died with prostate related problems as he understood that he had been using a catheter.

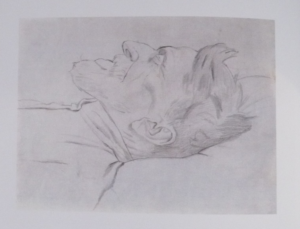

At that time the family were living in St Petersburg or Leningrad in an apartment at 19 Literatov Street. Ekaterine knew that in the same block an artist lived and she sent Pytor her youngest son to ask the artist to do a drawing of Esper on his death bed. That artist was Pavel Filonov, a noted avant-garde artist. His work is not well known outside Russia since few of his works left Russia.

Filonov produced a drawing of Esper but would not accept any money for his work, Ekaterine offered to teach him English by way of payment.

In 1924 the journal Katorga i ssylka (Hard labour and exile), which published material by and about political prisoners and exiles of the Tsarist regime, carried a tribute to Esper:

“..a bright person, who made no compromises, which undermined the foundations of his views, invariably sympathetic to the joys and sorrows of his comrades, a man who loved people, and of faith in the triumph of social equality and freedom.”